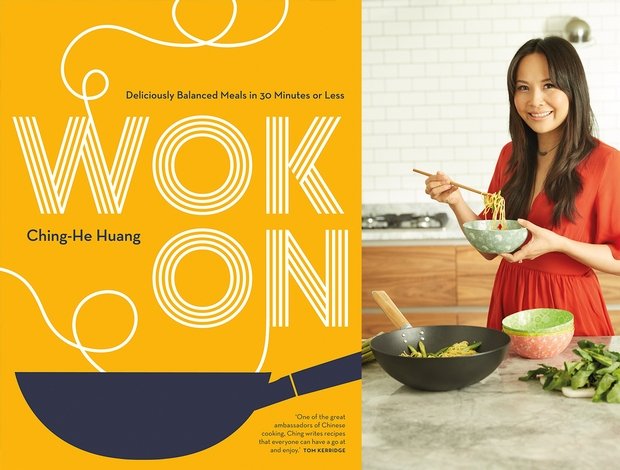

Having presented many modern Chinese cookery shows for over a decade, Ching He Huang is a familiar face on British and international screens. She’s also an award-winning cookbook author, with eight bestsellers to her name, including her 2019 publication, ‘Wok On: Deliciously Balanced Asian Meals in 30 Minutes or Less’. Born in Taiwan and raised in South Africa before moving to London aged 11, Ching graduated with a first class degree in Economics then went on to set up her own food business. In this interview, Ching talks about the challenges of being an entrepreneur, the lessons her travels have taught her, her experience of apartheid and juggling multiple careers.

What was your experience of growing up during apartheid in South Africa?

It was very difficult. I was five when we emigrated, so I didn’t speak a word of English. It was culturally closed: when you’re a young child and you’re in a new environment, you can somehow sense the vibe, which wasn’t so friendly. It was a cruel place, and children can be quite cruel as well. But as humans, we sometimes fear the unknown. Over time, my brother and I fell into place and made friends at school, but it was very tough at the start. It was the biggest challenge as a child, but you’re also very strong at that age, and innocent; you find the beauty in people.

We were there for almost six years, and I’ve been back a few times since we left. South Africa is a beautiful country, but it still has many issues and prejudices, so I wonder when that cycle will come to an end. The walls have to come down at some point; everyone is living in fear of one another. Hopefully the climate crisis will unite everyone together in a common goal.

How did working 16-hour days, 7 days a week, for 3 years, to establish your catering company affect your mental health and what lessons did you learn from this intense phase of your life?

I’m not going to lie, it was really tough to set up a business. I was in my early 20s, so I had a lot of energy, but it broke me several times mentally: I didn’t make any money for the first three years and just about broke even; trying to find money; trying to make the cashflow work; trying to support, pay and hire and fire staff; inspiring them to use their own initiative so that I didn’t have to hand-hold them; trying to find new customers because I’d win contracts then one would go the next year because I’d built their business up so much that they needed a bigger supplier!

Then there were other issues: drivers being late; controlling the temperature as I was a high-risk ready-to-eat manufacturer; dealing with the price of chicken going up; sourcing lettuce during the summer where we had shortages. What do you do in those situations? You’ve signed all these specs with clients, caterers and retailers and everything had to be perfect: there was no room for error.

“It’s about consistent hard work: nothing comes overnight.”

Then about four years in, I had the opportunity to go into TV, so I was building two careers simultaneously. We also moved our kitchen from North London to East London, which was a massive disruption, and we only had a month to do it. There was so much pressure to complete and exchange during the quiet period between Christmas and New Year between Dec 2003-Jan 2004; it was the most stressful time of my life. Then the TV stuff started picking up as well, so I was running around in all directions. But it really made me strong and now I tell anyone who’s trying to chase their dreams not to give up. If you’re doing a day job that you’re not passionate about, you should definitely look at doing something else and build your second career. So many young people are doing the 5-9 now, i.e. doing what they love after work. Slowly, the thing you want to do will overtake and then you just drop the other one, which I what I did after ten years! I’d had enough and I went into TV full time, but TV work is also few and far between and so it’s about consistent hard work: nothing comes overnight.

A lot of experiences never leave you, but I advise trying to find peace and some quiet time; don’t just keep going and burning. You need to nourish yourself mentally and physically, so that means good food, good sleep, seeing friends and a change of scenery. Talk about your problems, and also cry if you have to because it’ll make you feel so much better.

What were the biggest challenges that you faced as an Asian female chef starting out in a male-dominated industry and how did you overcome them?

You can always sense when people don’t respect you from the way that they behave around you. Whenever I’ve worked in restaurants, chefs look at me and you can tell that they’re thinking, “What’s this girl going to do?” from the look on their faces. Let the work speak for itself. If you do good quality work and know your stuff, then they start to change their minds and respect you. If you also go in with prejudices, you won’t get anywhere. It’s all very sensitive when you’re dealing with people’s passions, livelihoods and their art and voice. My advice is to be consistent and persistent.

You’ve written several successful cookbooks. What do you like and dislike about the process?

I love the process of writing and creating; thinking about recipes really fuels my fire. It’s wonderful to have time to myself, sit down and look through some of my past books to avoid repeating anything. I want to bring a fresh perspective each time and give people something new to try. I was keen to do ‘Wok On’ because I feel that there are many recipes that I’ve omitted from various shows and previous books which should be at the forefront, such as Macanese dishes which have a Chinese influence. This emphasis on regional cuisine is incredible; everyone has a story to tell. We’re now going deeper, so we’re mining for the truth.

“I’m quite an impatient person and that’s reflected in my recipes!”

I want all my recipes to be accessible and easy, which is what has always felt instinctive to me. It doesn’t make sense when it’s overly complicated. I’m quite an impatient person and that’s reflected in my recipes! I think, “How can I get to the most delicious dish in the shortest possible time with the least amount of ingredients?”

The most difficult part is the back and forth process of book writing. Once I’ve gone through the whole book, I’ll get an email saying, “Can you please check it again?”

Apart from your own, which books do you gift most often to family and friends and why?

The book I give the most is ‘Eat Clean’. It was actually my biggest failure in terms of sales because back then, I don’t think people understood the message. There was a backlash against clean eating, but my philosophy behind this book was different. I guess the title was unfortunate. For me, ‘Eat Clean’ was about organic produce, free from pesticides and artificial ingredients, considering provenance and listening to your body. It was a more holistic approach, not simply cutting out food groups that you think will make you fat! The clean eating trend came from a place of vanity as opposed to supporting your immune system or giving you optimal health and balance.

I also gift a lot of books like The Secret and Conversations with God by Neale Donald Walsch – a must.

You described 2012’s ‘Exploring China: A Culinary Adventure’ with Cantonese chef Ken Hom as “the most enjoyable television production”. What did you love so much about it?

This was such an adventure for me, and an achievement. But it was a terribly painful process: five and a half weeks of non-stop travelling with no breaks! I’d just finished two productions in the US – Easy Chinese and a Chinese New Year Special for the Food Network, plus an Iron Chef competition with another chef, which killed me as I was his sous chef – and I went straight back to London, picked up my bags and headed to China for five and a half weeks. Mentally, I was exhausted, but when you’re trying to achieve something, you’re on a treadmill. When you step off it at the end and look back, you feel an extraordinary sense of achievement and satisfaction. You didn’t know that you were capable of doing it, so you’re constantly breaking your own barriers and testing yourself.

I also met the most amazing chefs, and not just in restaurants, but humble cooks who do this day in, day out. They probably think they’re not doing anything special, but to us their creations are a revelation and source of inspiration. I encourage people to travel, open their minds and immerse themselves in the food: the more you taste, I think the more you understand culture.

Your work has taken you around the world. Of everyone you’ve met, who has made the biggest impression on you, either professionally or personally, and why?

The most inspiring thing is when I see someone with nothing create something that means everything to them. I can really relate to this because I come from a very humble background – my grandparents were farmers on both sides; my father had to work so hard to emigrate twice, first to to South Africa then to England – so I love when chefs bring their dedication to their cuisine.

There’s a chef in Beijing where Ken and I filmed in one of the best Peking duck restaurants who must be close to 80 years old now who told us that after the cultural revolution in China, he had nothing. Their building was completely destroyed and they had to literally rebuild their home from scratch: go out into the field to pick up bricks one by one and use a basic cart to drag them back. Now everyone recognises him, with presidents from all around the world visiting his restaurant. I don’t know what’s more inspiring than a story like that: he and his family went from nothing to international recognition. That will always stick with me.

How do you choose your philanthropic projects and what does each one represent for you?

I love helping where I can; it’s important to give back because there’s only so much material stuff you can achieve and beyond that, it doesn’t mean anything. You can’t take any of it with you.

I grew up with Tzu Chi, a Buddhist foundation in Taiwan, when they had a chapter in the UK, and it’s all about giving back, culture, education, climate and so on. I love that it was started by a female nun, Master Cheng Yun, in Taiwan who began by making socks in her village and selling them to the locals to raise money for their foundation. She believed that Buddhism should be in action. Some charities will just ask for money, but if you say you’re a good person, you should demonstrate it, and they give people the opportunity to demonstrate compassion.

Tzu Chi had very humble beginnings and now their influence is huge. They sustain themselves by selling Master Cheng Yun’s books and other products, such as clothes made from plastic. This supports their marketing efforts, but any external donations are given to relief projects, e.g. floods, earthquakes, etc. around the world. Volunteers pay to go and deliver the aid themselves, so none of the charity’s money is being used for purposes other than giving direct aid to those who need it the most. I really believe in what they do and it’s a charity that’s very close to my heart.

“Even it’s a kind word, nothing is ever too small.”

In the UK, I’ve recently become an ambassador for Centrepoint. They’re doing very well, but they still have a target this year to raise £3 million to build 300 homes for people aged between 16 to 21. I was almost homeless once as well. When we moved to London, my father ploughed everything into escaping apartheid. We arrived in 1989 and in 1990, the recession happened. By then, my father had spent £250,000 to get an entrepreneur’s visa and he lost everything. That’s how I started cooking when I was 11. My mother had to go away for work a lot and send money back, my father was trying to make ends meet in London, so when I was 15, I lied to get a job in Next in Brent Cross Shopping Centre because we were on the verge of losing our house.

My parents put us into private schools, but it was a financial drain. I remember my headmistress coming into the shop on a Thursday evening and I opened my big mouth and said, “Oh, hi, Mrs Pond!” She asked me what I was doing there and I told her that I had to work on Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings to help my parents and that I’d have to leave after sixth form to find work. The following day, she said, “If you get good GCSEs, I’ll give you a scholarship.” She changed my life and is the reason why I advise people to do something that’s going to change someone’s life. Even it’s a kind word, nothing is ever too small.

Have you ever tried a dish in another restaurant or at an event that you wish you’d created, either in London or elsewhere, and if so, what made it memorable?

I recently returned from the south of France where I had this delicious egg, truffle and mushroom dish, so a steamed egg loaded with caviar with a huge range of seasonal mushrooms inside. I’m really jealous of the chef’s creativity because I think it’s such a brilliant idea! I would do a Chinese steamed egg with seaweed, shitake mushrooms and Chinese caviar, the luxurious Chinese ingredients we hold dear. Although I’m envious, I feel like I have been inventing and creating in my own way.

As an advocate of fusion cuisine, what’s your view on cultural appropriation in food?

When I first started cooking on telly, I would put Shaosing rice wine in almost everything, because my grandmother used to and that’s what I was taught. But I had Chinese cooks writing in saying we don’t put it in every Chinese dish, which is of course true, however it wasn’t authentic to my style of home-cooking and my family’s roots! Now you can find Shaoshing rice wine in a Sainsbury’s Local on the high street on The Strand (expensive rent) – funny how ingredients become the norm over time.

Deep down, because of everything that I’ve been through, I feel like it’s not impossible from people from a different culture to fall in love with another through cooking. They say if you spend 10,000 hours on a subject that you’re passionate about, you can be an expert. Food is there to inspire people and enable us to learn from one another. Whenever people ask me for an authentic restaurant or dish, I tell them that they’ll never find anything like that because nothing is authentic!

In China, we never used to have sweetcorn or chillies; these were all imported. The same thing with potatoes – the Chinese government encourage the population to eat more because you get more yield per square metre of land, making it more sustainable. Now potatoes are everywhere; we even have a potato bun! It looks like a jacket potato stuffed with Chinese filling. In a few years’ time, we’ll be saying the potato bun is authentic to China! If you’re going to dabble in someone else’s cuisine, make sure you do the research. Consult people from that culture and collaborate with them, engage with them, and then maybe there wouldn’t be all this drama about authenticity.

You’ve been quoted as saying, “To me, time is a real luxury.” If you were magically given more time, what would you do and for what reason?

I’d write another book, which I have to do next year. We haven’t come up with a title yet, but we need to be more green in terms of our health, wellbeing and for the planet. I’d also paint all the subjects which interest me, and do all this while trying to remain a sane human being!

If you hadn’t carved out a career in food, you’ve said that you’d be writing children’s books. What would they be about and what about this activity appeals to you?

I don’t have any children, but I love my niece and nephews, and I love books. I also love painting, so anything creative appeals to me. I enjoy telling stories and trying to expand their minds. Instead of trawling through things on social media, which is a time drain, I want to give them something more meaningful.

How do you feel you’ve changed as a person over the last 5-10 years?

I try not to take things too seriously, or too personally, to be more in tune with myself and my goals and to learn the art of growing up, so doing what I should be doing for myself. I’m less competitive now and more true to myself. I try to worry less about what other people think or what they think I should be doing. I’m trying to be more present in the moment and be more zen about everything. I want to avoid putting myself under too much pressure and forgive myself; we’re human and we have flaws. It’s about acceptanceand movingon. I also don’t want to take anything for granted and continue to work hard towards honouring my passions and truths.

If you enjoyed this Ching He Huang interview, you can read the rest of the interviews in the Spotlight on Chefs series here.

LINKS

Ching He Huang, Wok On, Salsify at The Roundhouse Review (Cape Town), Stephen Raaff Interview, Nokx Majozi Interview, A Taste of Hong Kong Review, Ravinder Bhogal Interview