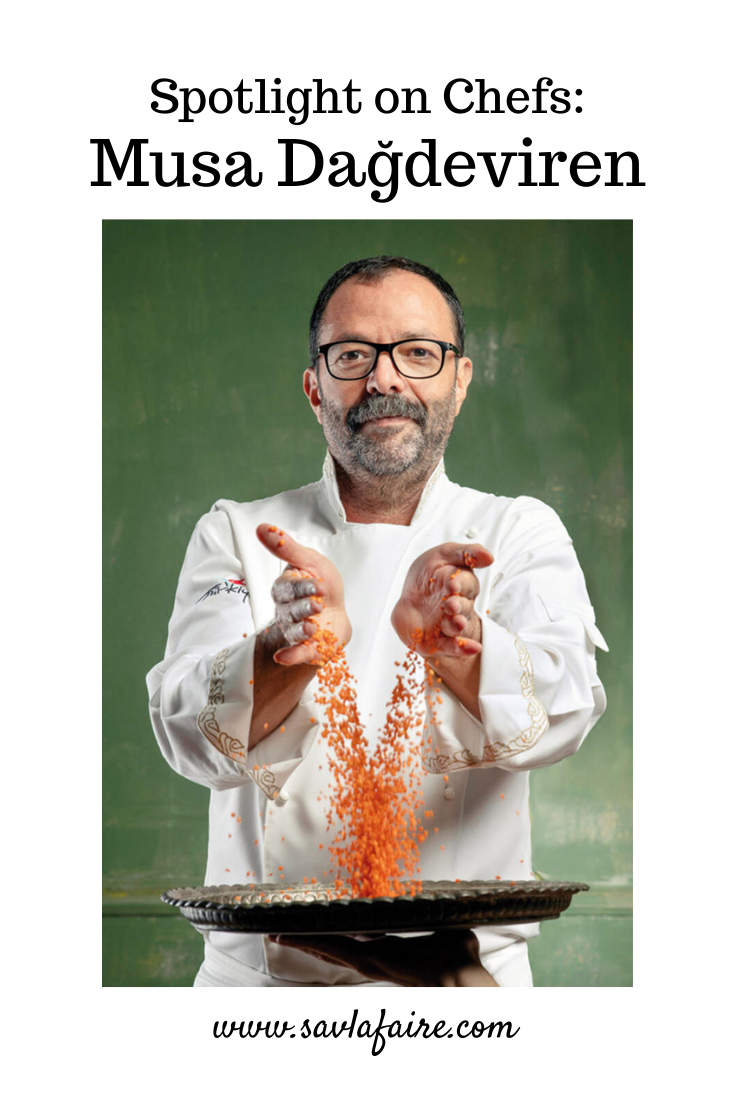

Musa Dağdeviren and I met in January when the Turkish chef hosted a dinner showcasing traditional recipes from his award-winning book, The Turkish Cookbook. Each delicious dish was accompanied by riveting stories about their heritage, the techniques used to create them and the people who still enjoy them today.

The evening, organised by the Yunus Emre Institute which has been passionately promoting Turkish art and culture in London since 2010, was part of the ‘A Pinch of Anatolia’ series. The aim of this project is to celebrate Anatolia’s 13,000-year-old culinary history, which is perfectly aligned with Musa’s own objectives. As well as being a successful chef, restaurateur and author, he is a Netflix star, having featured in their popular Chef’s Table series. I sat down with him to talk about his newfound fame, having his own publishing house and diners’ reactions to his food.

In the early days of Çiya when you were working day and night and sleeping on the restaurant floor, what made you keep going and refuse to give up?

It was my passion and that passion motivated me. I believed in what I was doing and loved every moment of making my dream come true, even the tough times. I never once thought about giving up, and I still feel happy and excited when I cook now.

There was a lot of opposition to Çiya and what we stood for at the beginning because people looked down on restaurants like ours. There was considerable prejudice: people said that no-one would eat this kind of food. When we mentioned local cuisine, the immediate association was gözleme [traditional filled Turkish flatbread] with cheese or meat. When they understood that we were offering much more, diners rushed to the restaurant to try the menu.

Our success made hoteliers, cinematographers, anthropologists and chefs realise that they’d overlooked this part of our culture and history and they too embraced it. In fact, 30% of our customers are chefs or from the hospitality industry. We also have many food critics, teachers and ethnobotanists, e.g. mushroom specialists. They all come to Çiya to study our dishes in detail.

When you see people enjoying the traditional Turkish dishes that you champion, whether that’s at home or abroad, what does it mean to you?

Cooking for ‘A Pinch of Anatolia’ event organised by Yunus Emre Institute at Turkish restaurant Laz Camden was the first time I’ve cooked in a Turkish restaurant abroad. Until then, I’d only done demos for the Culinary Institute of America or participated in social projects. I’ve also been to award-winning restaurants in Chicago and LA to promote my book and give speeches. But it was much more meaningful to cook in a Turkish restaurant for diners as it gives me a stronger sense of purpose. When people pay for this experience, they know where their money is going.

Some of the dishes on Çiya’s menu have been forgotten in their places of origin. We have very old customers who come to eat the food that their grandmothers used to make for them when they were five years old. When they rediscover those flavours and the memories come flooding back, they’re completely overwhelmed: their voices get louder and the tears start flowing. Then when neighbouring tables witness this scene, they get caught up in the emotions as well. These customers sometimes bring me gifts from their kitchens to thank me or share their old family recipes with me.

Could you please retell the story of “bear mushrooms” from that evening?

You can find thousands of these mushrooms, which are porcini mushrooms, in the Marmara region and in the western part of the Black Sea region. Top-class Turkish restaurants are unaware that they grow in these areas and instead speak passionately about porcini mushrooms from Italy. Wealthy Turkish diners also like to play a game of one-upmanship, saying that they’ve eaten certain ingredients in certain places around the world. It’s all very sad.

This mushroom grows after the rains in September. Some producers dry them out, package them up and export them to Bulgaria, where they put an EU stamp on them. They usually cost 10-15 Turkish lira before being packaged and stamped, but can cost anything between 100 and 300 euros afterwards. In restaurants, the mushrooms will be sautéed with onions, folded into a crêpe and then topped with Parmesan, transforming them into something more refined. The name and description of the dish are made to sound really exciting and people pay serious money to eat it. If you told them that it was made with local mushrooms and cheese, they’d only pay 3 lira for it, or may not even want it.

“It’s such a shame that we’re so disconnected from our country and culture.”

It’s such a shame that we’re so disconnected from our country and culture. Actually, there’s no difficulty in generating interest among the less fortunate members of society or those living in rural areas as they’re enjoying this produce and keeping traditions alive. In big cities, however, people are more intrigued by Western European and American cultures than their own and therefore tend to lose their own identities. They’ve become victims of consumerism.

The Turkish Cookbook features 550 recipes accompanied by the fascinating stories and culinary practices behind them. How did you decide which ones to include?

I originally had 1,200 recipes for the book, so my publisher suggested that I split them over two volumes to be released at different times. Selecting the recipes was such a difficult task: it’s like choosing between your children! I was picking one and then feeling sorry for the others.

Among the final 550, there are some traditional dishes which people may be familiar with, such as Kadınbudu Köfte (Ladies’ Thighs Meatballs), Hünkar Beğendi (Lamb With Aubergine Mash), İçli Köfte (Kibbeh), Keledoş (Lamb, Curd and Sorrel Soup) and Çorti Aşı (Stewed Goat with Pickles). City dwellers will have never come across these types of dishes. In the book, I’ve listed them by the main regions, e.g. Istanbul and Ankara, and then categorised them further.

I also included seasonal food and festive meals, all accompanied by notes about their heritage and rituals. For example, in the Marmara region, whenever there’s a wedding, the bride’s side steals a chicken from the groom’s side for a bit of fun.

Then there’s Aşure (Noah’s Pudding), which is only made at a specific time of the year and this tradition has been maintained for hundreds of years. Some dishes evoke nostalgia and you eat them to remember the past.

How has life changed since you appeared on the Netflix series Chef’s Table, if at all?

I’m still the same person, but there has been one major change: people come to Çiya to take photos with me now! I can’t refuse as it’s a nice thing to do for them, but it can become too much sometimes. I think it’s incredible that we have so many international customers. The Netflix fame hasn’t affected me in any other way: I’m still a chef and I still make food as I’ve always done.

Tell me more about Çiya Publishing, your own publishing house, and what you do.

I set up Çiya Publishing many years ago and every quarter since 2005, we publish our Food and Culture Magazine featuring recipes from cookbooks dating back to the early 18th century, which were written in ancient and modern Turkish, plus articles on anthropology, agriculture, etymology, etc. I speak at many universities and conferences on these topics to raise awareness, as well as contributing to the magazines, sharing my field studies and debunking popular food myths. In each edition, I also include a list of seven forgotten foods with their recipes. The other contributors are all academics and therefore highly specialised in their fields of expertise.

What do you think is the most important contribution that Turkish cuisine has made globally in terms of ingredients, techniques, dishes, etc.?

In each Turkish region, there’s a version of pastırma (Cured Beef) which is comparable to Italian pastrami, but the cooking techniques differ from one kitchen to another.

It’s hard to give just a few examples, but the obvious one is döner kebabs, which can be seen everywhere, from South America to Western Europe. They may not be made in the traditional way, but some countries have fully adopted them: döners are a national favourite in Germany and Mexico, for example! They’re enjoyed far beyond the local Turkish communities in these countries; immigration enables people to share cuisines, learn from one another and exchange ideas.

“I’m not against fusion food, but we must respect traditions.”

Before the 15th century, we didn’t use aubergine in our cuisine, but then it was brought over from India and China. We were introduced to okra via West Africa, then potatoes and beans from America, etc. Over time, all cultures have taken non-native ingredients and incorporated them in their cuisines in this way. As such, I always talk about food in the context of its geography instead of referring to nationalities and race.

I’m not against fusion food, but we must respect traditions. When you cook İmam bayıldı (Vegeterian Stuffed Aubergine), there are four cooking techniques. If you don’t know them, you can simply fry the aubergine and serve it on bread, but you can’t refer to it as İmam bayıldı because it’s not the same. It’s fine to get excited about making and eating fried aubergine on bread; there’s no problem with that. The most important thing is that whatever the chefs’ origins – Turkish, Indian or Iranian – they must be familiar with both traditional and local cuisine.

What’s your most valuable possession, how did you acquire it and why does it mean so much to you?

The thing I value the most is old documents about the past and recipes; they’re physical evidence of our history and traditions. I love learning something new about our country, cuisine and culture and will never get bored of this. It’s so exciting to discover new ingredients and techniques.

What’s the best piece of advice that you’ve received and why has it stuck with you?

My mother is the most important person in my life. I always wanted to copy what she was doing in the kitchen and she truly influenced the way I cook. I’ve always tried to replicate her dishes, but I can’t quite recreate the magic. Early on, as I mentioned in Chef’s Table, she told me that I was “the seed” [who would keep their traditions alive].

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. If you enjoyed it, you can check out the rest of the Spotlight on Chefs series here.

LINKS

Ömür Akkor interview, Yunus Emre Institute, A Pinch of Anatolia, Asma Khan interview,

PIN FOR LATER